Chinese Painting and Calligraphy

Most of what I know is self-taught, by coping from books and practicing everyday. Upon coming to China, I studied Chinese calligraphy (specifically the Li style calligraphy, 隶书) with a Sichuanese master, Hou Kai-Jia. Chinese art is linear in the extreme sense, i.e. a single line (brush stroke) can form an image (e.g. a stalk of bamboo) with variations in line thickness and darkness. In this sense, the writing of Chinese characters forms the basis for all Chinese art: a master of the basic strokes (there's only a dozen or so) and four basic calligraphic styles (Zhuan 篆, Li 隶, Kai 楷, Xing 行, Cao 草) has little trouble with painting rocks, birds, etc., for these are just "characters" too. Don't underestimate the subtle form and balance of a Chinese character, however. Aside from the form of each of the stroke, which has rigid specifications (except for the free style Cao), the separate elements of the character must visually hold together without too much white space or crowding. Take one of the simplest characters, the word for "mouth", which might be described as a `box' (see first character below)

|

|

|

|

It is not just a box however, and if you write it in one stroke that way it will look very wrong. There are in fact three separate strokes, not entirely symmetric or 'lined up', which might look sloppy if you're used to Roman characters but is totally organic and good in the Chinese aesthetic. Now, the reason there are so many Chinese characters is that any two or more characters can be combined to make another one! It doesn't take a genius to realize there is infinite growth potential here, and in fact new characters are being created all the time! Our 'mouth' character is thus also found embedded inside many other characters, (see above) but notice how the position, size and proportions change depending on its embedding. Now, the specific rules governing how to write a character have never been quantified as far as I know. You just have to copy the master (or a calligraphy book) and acquire the intuition. I strongly believe, however, that the rules for writing a visually attractive character could be objectively determined, and maybe someone someday will do this, using perhaps geometry and principles of gestalt psychology (e.g. human art seems to have a bias for objects 'just touching' as opposed to 'just not touching', see second character above).

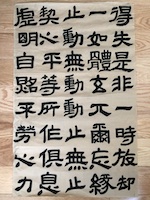

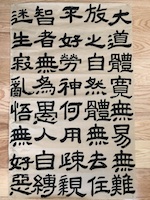

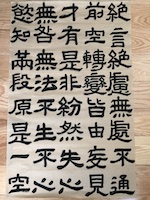

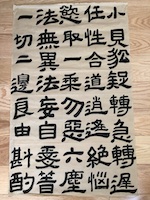

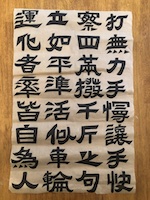

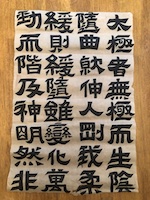

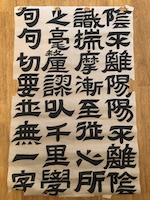

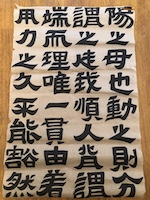

Below is a sample of some of my own work:

watercolor |

"The Great Way is Wide" |

"Not Easy, Not Hard" |

"Honesty Pays" |

"Keeping Form is Greatness" |

| Xin Xin Ming (wall mural) | Heart Sutra |

Tang poem |

Chop (copper) | Chop Images |

Buddha (cinnamon) |

Skateboard (carved) |

"Selfless charity" |

Chop (soapstone) |

Chop (obsidian) |

|

Xin Xin Ming (wall mural)

太极者,无极而生,动静之机,阴阳之母也。 动之则分,静之则合。无过不及,随曲就伸。人刚我柔谓之走,我顺人背谓之粘。动急则急应,动缓则缓随。虽变化万端,而理唯一贯。由招熟而渐悟懂劲,由懂劲而阶及神明。然非用力之久,不能豁然贯通焉。 虚领顶劲,气沉丹田。不偏不倚,忽隐忽现。左重则左虚,右重则右杳。仰之则弥高,俯之则弥深,进之则愈长,退之则愈促。一羽不能加,蝇虫不能落,人不知我,我独知人。英雄所向无敌,盖皆由此而及也。 斯技旁门甚多,虽势有区别,概不外乎壮欺弱,慢让快耳。有力打无力,手慢让手快,皆是先天自然之能,非关学力而有为也。察四两拨千斤之句,显非力胜;观耄耋能御众之形,快何能为。立如平/秤准,活似车轮。偏沉则随,双重则滞。每见数年纯功,不能运化者,率皆自为人制,双重之病未悟耳。欲避此病,须知阴阳。粘即是走,走即是粘。阴不离阳,阳不离阴。阴阳相济,方为懂劲。懂劲后,愈练愈精,默识揣摩,渐至从心所欲。本是舍己从人,多误舍近求远。所谓差之毫厘,谬之千里,学者不可不详辨焉。